A SECOND CHANCE FOR REFORM

The PAP’s stunning election victory doesn’t mean its remaking is complete.

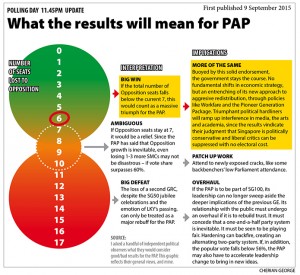

On election night in May 2011 – which now seems an eternity ago – I cautioned that the opposition and its supporters shouldn’t get carried away by its stunning victory. Anyone who assumed that there was now an unstoppable momentum towards a two-party system might be overestimating the opposition, misunderstanding the electorate, and underestimating the PAP, I suggested.

This weekend, four years on, it may be time to bequeath the wet blanket to a jubilant People’s Action Party and its fans. This is not to deny the scale and clarity of Friday’s result. The only things that rang hollow about the victory were PAP candidates’ programmed intonations that they felt “humbled” by it: in their mind’s eye, each was probably performing an exultant goalscorer’s medley of chest-thumps, knee-slides, badge-kisses and heaven-pointing. And who can blame them.

But, as with GE 2011, what is doubtful is how far into the future we can extrapolate the latest election results. The SG50 celebrations put PAP leaders in the mood to ponder the longue durée. But talk of this election taking us to SG100, aside from being Constitutionally whimsical, may be as premature as Low Thia Khiang’s 2011 claim that Singapore was now on the road to a First World Parliament.

What is certain is that the PAP has been given another five years.

What is possible, but not guaranteed, is that politics in the coming term may be less toxic than in the last.

And if it manages to “get the politics right”, to borrow Lee Hsien Loong’s oft-used phrase, the PAP may indeed turn out to be the lead author of the second half of the SG100 story.

That’s a lot of ifs. Whether it succeeds depends on what it does with the mandate that it has just been given.

To understand the PAP’s success and the risks ahead, we have to see 2015 in the context of 2011. By the government’s own (belated) admission, it had been guilty of serious policy missteps in the years leading up to the 2011 GE. After that election setback, it had to decide how to correct its course.

To some commentators, the situation called for urgent reform of its approach to governance, especially its habit of assembling undoubtedly capable but suspiciously like-minded individuals to make decisions, and insulating them from open competition and on-going scrutiny.

The government chose instead to stay within its comfort zone, getting creative in a number of policy domains, but stopping short of reforming itself. Indeed, probably in reaction to the merciless barrage of online attacks, the years 2011-2015 were marked by a circling of wagons, resulting in a degree of defensiveness and intolerance not seen for decades. Civil society activists, artists, academics and journalists witnessed a closing of the PAP mind, and a greater impulse to intervene in and control the flow of information and ideas. This was the exact opposite of what anyone with an accurate diagnosis of GE 2011 would have prescribed.

Thus, the PAP’s paradoxical playbook introduced a welcome softening in social policy, while hardliners stamped their mark on political space.

Persistent problems

It is a truism in office politics that, when things succeed, everyone will claim credit. Governments are equally prone to that tendency. So, we can expect many to be lining up for a taste of the spoils of GE 2015; and they won’t be satisfied with humble pie.

Few would disagree that, at the national level, credit belongs mainly to the architects of initiatives like the Pioneer Generation Package. Such schemes succeeded in reducing Singaporeans’ anxiety over costs, and providing them a much-needed sense of financial security and social justice.

But it is possible that the PAP’s GE post-mortem will also conclude that its hardline politics were vindicated. If so, the next five years will see a further increase in its political intolerance.

This could turn out to be a strategic error. To see why, we again have to revisit 2011 and its aftermath: in particular, the reform path that was not taken.

Even within the wider establishment, there were many who admitted that the pre-2011 mistakes pointed to a structural problem. The government’s system for absorbing, interpreting and responding to criticism and bad news from the ground had failed. Nothing else could explain the fact that policy makers were insensitive to the pain being experienced by ordinary Singaporeans, until they expressed it at the ballot box.

This didn’t produce only fixable policy lapses, but also a longer-term trust deficit, which has been much harder to bridge.

According to PAP doctrine, a key hallmark of good government is an ability to persuade citizens to accept short-term pain for the long-term interests of the country. In 2013, it failed that trust test. The Population White Paper was the most important masterplan that government leaders needed to sell in its 2011-2015 term. They believed it to be fundamentally sound, but too many Singaporeans didn’t believe them when they said so.

Is the PAP today any more capable of calling on the people’s trust than it was in 2013? Possibly, but it would be presumptuous to take that for granted.

Another weak spot that the election results should not obscure is the quality of the PAP’s self-renewal, which is one of the core goals for which it wanted a strong mandate. It now has that endorsement. But it is somewhat disconcerting that all three new MPs-elect identified for high political office were inducted on the basis of their performance in the public sector. So are all four fourth-generation leaders from the 2011 cohort.

As Singapore faces more intense economic challenges, it is worrying that the PAP has been unable to attract private sector leaders who have proven themselves in building and running large organisations that are exposed to global competition. Given the size and complexity of the Singapore economy, it is inconceivable that such talent does not exist.

A party in denial would argue that none of this is its own fault. Government can’t compete with private sector remuneration, it might say. And the political environment, poisoned by social media, makes good people unwilling to sacrifice their privacy.

But there may be other reasons. Cabinet’s composition may have already passed a tipping point, such that it is dominated by public sector groupthink. (Singapore public sector leaders are of course convinced that they do not suffer from groupthink, and this conviction may be precisely the force field that makes their culture impenetrable.) Original thinkers with strong personalities in the private sector – a future Lim Kim San, for example – may feel unable to contribute in such a milieu. Whatever the reasons, the homogeneity of the next generation leadership merits a red flag.

GE 2015 offers the party a fresh opportunity for reform. It must, of course, continue with its match-winning social policies. But it can afford to abandon the other half of its “new normal” playbook, which saw government leaders employ hardline tactics that may have made their own jobs easier – without making Singapore better.

Short-circuiting debates and stifling critics are the best ways to make policy formulators shoddy, and thus replicate the Population White Paper fiasco. Conversely, more vigorous debate in advance should produce more resilient and robust policy ideas. It may also persuade potential leaders who are used to more competitive environments that the governing elite is not a closed shop.

Therefore, the ruling party needs to embrace the principles of open government, which would include institutionalised, transparent mechanisms to ensure that government bodies work in the public interest, such as an Ombudsman’s office, more independence for statutory bodies from executive interference, and more protection for dissenting views.

Why now

The PAP is still dominant, and it would be smart to institute reforms from a position of strength than wait till its back is to the wall.

Some think that the PAP is not capable of deep reform. But, to those who are optimists at heart, there are glimmers of hope. The government has one senior Cabinet member who has come through the bruising new normal with his reputation enhanced. Internationally and domestically respected, exceptionally competent and trusted even by opposition sympathisers, he is uniquely positioned to lead a political reform process.

And among the latest inductees for political office, there was at least one battle-scarred high-flier who was prepared to talk during the campaign of a “New PAP” that welcomes a “genuine diversity of opinions”.

Alternatively, it could just dig in even more. It’s their party; they can try if they want to.

But if so, future electoral success would depend on continued, uninterrupted delivery of economic goodies – a purely performance-based social compact devoid of deeper loyalty. This is fine as long as the good times last, but will always be prone to another 2011-style shock and the bitter politics that follows.

Politicians who are more accustomed to winning debates by silencing dissent may find it difficult to adjust to open government reforms. But PAP leaders may wish to digest the same advice it has been dishing out to the citizenry: please don’t burden future generations with short-term, self-serving decisions you make today. If the PAP of the future is to be an integral part of a happy SG100 story, such are the sacrifices its SG50 leadership should be prepared to make.

On a personal note: An early reader of this article pointed out that some may see it as self-serving, since I am one of those who would directly gain from more space for criticism. That is true, but I would just add that any such benefit would be purely non-material. Since I live and work outside Singapore, any contribution to debates back home provides me no professional advantage, and is undertaken solely with my responsibilities as a citizen in mind.

RELATED

The hypothetical dream team would face a Catch 22. They cannot reform the party fundamentally until they reach the top. But they cannot reach the top unless they shed their revolutionary ambitions. Thanks to the cadre system, it’s only with the blessings of the current leadership can they climb the party hierarchy – and the current leadership is unlikely to sanctify young turks with radically different views. – AirConditionedNation, 3 January 2013.

Comments are closed.