BEGINNING OF THE END?

What the Punggol East result says and doesn’t say about the future.

Predictably, the Workers’ Party’s decisive victory in Punggol East has prompted speculation about whether this spells doom for the People’s Action Party in the 2015/16 General Election.

Such thoughts – wishful or alarmist, depending on your point of view – are unrealistic. First, GRCs do not behave like single seats. It is much harder to produce big swings in mega-constituencies than in a ward like Punggol East – a fact overlooked by Alex Au in his thought experiment on the effect of a national 10-point swing.

More importantly, such extrapolation overlooks one of the main characteristics that the Singapore electorate has revealed about itself in election after election. It wants opposition – but not just any opposition. Parties and pundits have consistently underestimated how discerning the electorate will be. In the run-up to last weekend’s poll, we wondered if Kenneth Jeyaretnam and Desmond Lim would split the opposition vote or confound swing voters so much that they would eventually stick with the PAP. In the end, the lack of opposition unity didn’t matter because voters made up for it with their singular focus on the most serious opposition team.

We can expect the number of high-quality opposition candidates to grow dramatically by the next GE, but we still won’t see them blanketing the whole island. For every constituency with a Lee Li Lian or Chen Show Mao taking on the PAP, there will be one or two others where the opposition candidates are just so-so or just loco. These individuals are not going to get the kind of swing that the WP enjoyed over the weekend.

A scenario that is more sober but still gamechanging is a major increase in opposition representation, but with the PAP still firmly in power. Arguably, this is the endpoint that Singapore’s middle ground has in mind. The WP leadership seems to think so, too. Its response to its latest victory dismissed talk of replacing the PAP, positioning itself as an effective check to keep the ruling party on its toes.

The PAP has tried to argue that it already has enough incentive to perform – primarily from its innate desire to serve – and that there are enough alternative voices in Parliament, thanks not only to the elected MPs but also NCMPs and NMPs.

If Punggol East voters speak for the country, it’s clear that Singaporeans don’t quite agree with the PAP that the right equilibrium has already been reached. Until an acceptable balance is achieved, we’ll continue to see the electorate practise a kind of affirmative action in favour of the opposition, with its candidates constantly given generous benefit of the doubt while PAP candidates are punished for verbal slips, or even just for their facial expressions (the “arrogant smirk” that Yawning Bread detected on Koh Poo Koon’s face might have been read as cool confidence, and the “fixed plastic smile” as understandable nervousness in front of the cameras, had Koh been wearing the Hammer badge).

What then is the “right” number of opposition MPs? My guess is that it is much higher than the current 8 percent of Parliamentary seats, but maybe not as high as 40 percent – the proportion of Singaporeans who voted for the opposition in the last election. As the number of opposition MPs rises beyond 20-30, you’ll see more voters wary of a “freak” result ousting the PAP entirely, and becoming more conservative. You could also see the PAP reforming itself dramatically, giving voters less reason to reject its candidates.

If the opposition grows to occupy more than 40 percent of the House, it would be because of a major slide in the performance of the PAP, which is of course not beyond the realm of possibility.

Even if the opposition collectively claims more than half of the seats, this may not spell the end of the PAP in government. It depends on whether the opposition parties are willing to form a coalition. As the Punggol East campaign showed, nobody should assume that just because opposition parties are repelled by the PAP, they are attracted to one another.

I don’t think it’s preordained that if the WP had to choose between the SDP and the PAP in a hung Parliament, it will opt for SDP. It could instead enter a grand coalition with the men in white, in return for a few Cabinet positions and legislative reforms, say.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should at this point declare that I am one of those who totally misread the Punggol East by-election, believing from start to end that the PAP would retain the seat. For more reliable predictions of future election outcomes, visit your local bookie.

But even if the eventual numbers are anyone’s guess, it is possible to make fairly firm non-quantitative predictions about how electoral politics will evolve over the next few years. Some of the dynamics were already apparent after the GE and last year’s Hougang by-election (see my earlier articles here and here). In addition, there are a couple of other developments to look out for.

First, we can expect to see the Workers’ Party attract several heavyweight candidates – including members of the establishment with some stature. This is a no-brainer, because the signs were already there in 2011. The WP’s most significant gain from Punggol East may not be the one additional seat, but the several fence-sitting, high-calibre potential candidates whose last remaining doubts about the joining the party will now evaporate.

Second, we will see the PAP torn between tactics. In the battle for Aljunied GRC, the PAP offered multi-million-dollar upgrading inducements, tried to tar Chen Show Mao as a foreigner and threatened voters that they would regret and repent if they kicked out the PAP. Voters kicked out the PAP, giving the WP 54.7 percent.

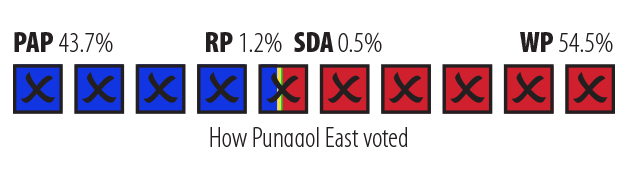

In the battle for Punggol East, the PAP fought an unusually clean campaign, with no personal attacks, bribes or threats. And? Voters kicked out the PAP, giving the WP 54.5 percent. Two different tactics, same result. Unfortunately, there goes the theory that if the PAP was just more pleasant, voters would like it more.

While the PAP is sure that its broad policy directions are in Singaporeans’ best long-term interests and that they will eventually realise it, you can hardly blame the party if it feels at a loss over what political tactics will keep it in power. Expect an internal debate between hardliners and moderates (though, given the party’s strong cohesion, we may never hear about it).

Thankfully, even the hardliners probably don’t believe that the old tactics of acting tough with voters can ever work again. However, how they treat opposition politicians, civil society activists and other real or imagined opponents is another issue.

Frustrated at the apparent lack of headway it’s making in public debates, some government leaders may decide that they have been too nice to their opponents. If they can’t control the demand for alternatives, they might be tempted to choke its supply, raising the barriers to entry for serious individuals who are tempted to join the opposition. I’d be happy to be proven wrong – but we should not be surprised if things get ugly.