LIVING UP TO OUR PLEDGE

This is the text of a presentation at the Institute of Policy Studies’ 30th Anniversary Conference on 26 October 2018.

In recent years we have seen countries with far longer histories of nation-building succumb to the politics of division.

Hate is suddenly a more potent motivator than hope in democratic politics.

This global pattern can’t be just coincidental. The best thinkers on this subject suggest we are at a world-historic inflection points, as significant as, say, the end of the Cold War. They say we are witnessing the end of the free market ideology of neoliberalism.

Pankaj Mishra in his book Age of Anger probably does the best job of analysing these times. He suggests that the 1990s neoliberal wave sparked aspirations among peoples everywhere that could not be satisfied, because they were based on a materialist ethic and mindless emulation, not genuine needs or sustainability.

The resulting resentment — a mix of envy, humiliation and powerlessness — is poisoning civil society, undermining political liberty, and causing a global turn to authoritarianism and chauvinism.

Mainstream elites and political parties haven’t found a replacement for the neoliberal order. The populists and demagogues who are filling the void don’t have a cure either; but what they do have is the snake oil of scapegoatism, and the salesmanship to hawk it effectively.

There is an economic debate to be had about this, but this is not the space nor am I the person for it. Instead I would like to reflect on the kind of political values that would best equip us for this age.

I want to suggest that Singapore’s horizontal, people-to-people relations, as well as our vertical government-people relations need strengthening.

National strengths

Before probing some of the weaknesses, though, I should emphasise that I don’t think the worst that we’ve seen elsewhere will visit our shores.

We do have some natural immunity to global trends.

One advantage we enjoy is that no single religion enfolds a majority of Singaporeans, which means politicians can gain no electoral advantage from religious nationalism. Second, we have compulsory voting; more than 90 per cent of the electorate habitually participates – and this means that election results are not prone to hijack by highly mobilised but unrepresentative groups while more reasonable people stay at home. Third, we are a city-state, so like most large cities everywhere we’re more inclined to cosmopolitan values, but unlike most cities these values are not in contention with a more homogeneous hinterland or economically backward regions where intolerant forms of nationalism tend to take root.

So my concern is not motivated by a fear of impending doom, but by the sense that our nation could be so much better.

Rampant individualism

We are certainly not spared the fundamental contradictions that always have plagued modern societies.

Our earliest nation builders recognised the tension between, on the one hand, enabling the pursuit of individual happiness and prosperity, which is essential for state legitimacy, and on the other, striving for the collective identity and cooperative instinct we need for national survival.

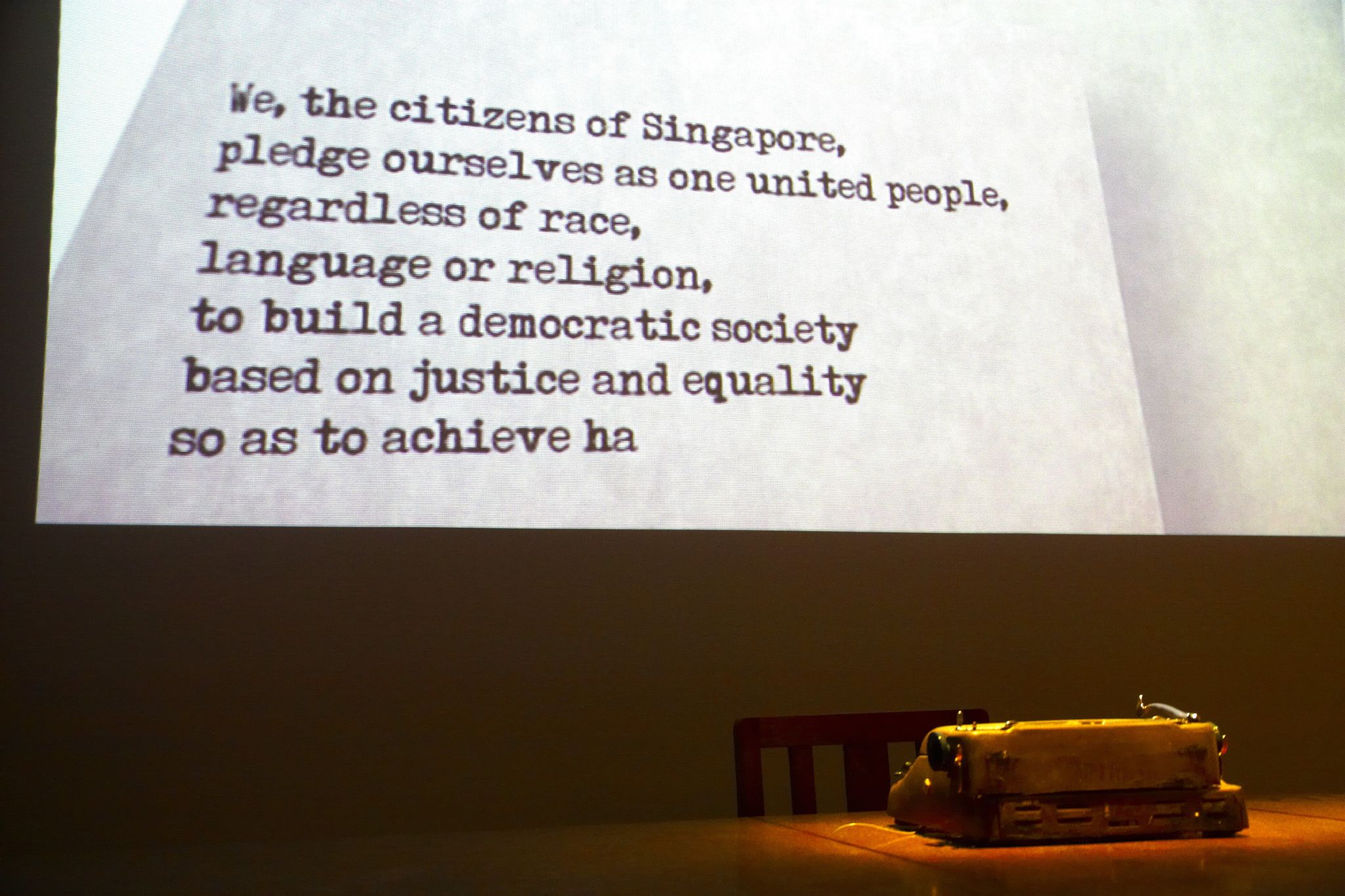

This is the concern at the heart of our 52-year-old national Pledge. The fact that we continue to grapple with this tension is in part a problem of success, in creating an island of opportunity for individuals and their families.

As individuals, we have come to equate progress with ever widening choice in material comforts and lifestyles. Social mobility for most of us means escaping the masses, out of the void deck into the country club; into ever more exclusive circles; where we can be increasingly fashion-conscious about what we eat and wear; finicky about the neighbourhoods where we live; and fastidious about our forms of worship.

When will religion regain its role as a champion of progressive values? – Click here for an extract from the Q&A

The rise of what Mishra calls “revolutionary individualism” and a “revolution of aspiration” was encouraged by Singapore’s embrace of neoliberalism in the 1990s, when the market became an ethic, not just a tool.

In the resulting privatised, gated version of the Singapore Dream, there’s not much room for other Singaporeans. Gotong royong is out, jealously guarded entitlement is in.

Live and let live is replaced by intolerance, by snobberies of class, culture and creed.

Approaches to diversity management

What should we be aiming for? What sort of unity or consensus should we aspire to as a diverse society?

There are at least three distinct ways of approaching the goal of national unity. The first is to think of it as a question of social order. This approach sees cohesion mainly as a security imperative. Ethnic diversity is regarded as a disadvantage, but acknowledged as a given we can’t erase, so we should at least make sure it doesn’t blow up in our faces. As for political diversity, there are fewer compunctions about flattening differences and forcing a consensus. When we view diversity through the lens of social order, we end up outsourcing its management to the state, along with other security problems.

A second approach emphasises the principle of reciprocity. We expect our rights to be respected but by the same token recognise the rights of others, even if this means we don’t always get our own way. We create fair and transparent rules for handling disputes, and will honour the outcomes of these procedures. The legitimacy of the system hinges on everyone’s equal ability to participate in it. In this worldview, it’s OK if we don’t always get our way, if at least we always get our say.

A third approach to managing diversity is based on a civic ethos, where people’s notion of the good life and a good society factors in the well-being others, including people very different from themselves. This worldview is in evidence when, for example, leaders and members of a majority faith instinctively rise in defence of minority religions that are under attack. Another indicator of a strong civic ethos would be when people are willing to support higher personal income taxes if it means that their children can grow up in a more civilised environment with more social justice and less poverty.

This is part of the social compact in some societies, and if it seems wildly unrealistic and idealistic in Singapore, well, that just goes to show that it’s not been part of our public discourse for a long time.

Back to basics

We shouldn’t think that a civic ethos is a totally foreign idea, though. It almost made its way into our national Pledge.

Go take another look at S. Rajaratnam’s first draft. It didn’t say what it now says, that the goal is “to achieve happiness, prosperity and progress for our nation”. No, it said, “we will seek happiness and progress by helping one another”. I actually find this a more meaningful statement than Lee Kuan Yew’s edited version, making much clearer what nationhood actually demands of us.

A strong civic ethos combined the principle of reciprocity form the best defence against attempts to divide us. They thicken our horizontal bonds. They are the antidotes to the law-of-the-jungle, might-is-right thinking being pushed by hatemongers around the world.

However, it is the realpolitik social order argument that tends to dominate the government’s rhetoric about managing difference. We have been taught for half a century to view differences of culture and opinion as a disadvantage, as potentially dangerous faultlines.

Vulnerability has become a national ideology, treating difference of any kind — race, religion but also political — as something to fear rather than celebrate. The management of difference is framed in negative terms: riot prevention.

This sort of thinking doesn’t permit horizontal, people-to-people trust to thicken. It feeds into the very kind of fear and zero-sum thinking — your difference is potentially at the cost of my well-being — that is being encouraged and exploited by populists elsewhere.

We should instead be cultivating the mentality that the Singapore whole is more than the sum of our different parts, that our diversity isn’t just a tourist attraction, but also enriches our own lives. And it is this net gain from diversity that makes a civic ethos not an act of charity or altruism, but of enlightened self-interest.

These ideas — of reciprocal rights, inclusive and fair processes, and of a civic responsibility to the strangers beyond our families and tribes — are essentially democratic values. It may seem odd to hitch our hopes to democratic values right now, considering the crisis some established democracies are in. Political scientists talk of a “democratic recession”, and it is indeed difficult to maintain faith in a one-person-one-vote system that has delivered Donald Trump, Brexit and a number of dangerous far right parties in Europe.

But the correct response to these events is to find ways to make democracy work better, rather than to abandon it and defect to Chinese- or Russian-style autocracy. That would be as rational as saying that your heart medication has got unpleasant side effects so you’re going to back to smoking.

Democratic values

Democratic values are still the best answer to, not the cause of, the self-serving individualism we’ve been talking about.

And this is not some contraband notion that I smuggled in on SQ21 from America yesterday. It too is an idea at the core of our national Pledge. When the founding fathers of our republic wanted a way to focus children’s minds on nation-building, on accomplishing unity in diversity, what did they do? They wrote a pledge “to build a democratic society”. Democracy, as they saw it, wasn’t the problem; democracy was the solution.

Of course the PAP continues to embrace democratic institutions insofar as reasonably free and fair elections give it the legitimacy to rule. There is also a non-trivial sense in which the formal Constitutional separation of powers is maintained.

But the Pledge doesn’t merely say we the citizens of Singapore will protect and preserve the democratic structures that have been given to us. No, it requires citizens to build a democratic society. It’s supposed to be an on-going, active process in which all of us participate.

Contained in our Pledge is the understanding that when we all collectively build a democratic society, when we think horizontally and not just vertically, we learn to recognise one another as equal citizens despite our differences; indeed, we discover we have mutual stakes in one another’s rights. My group protects your group’s dignity today, because otherwise we know we may be the victims of intolerance tomorrow.

This is what we pledge, but this is the meaning that has been hollowed out in the decades since those words were written. The PAP’s preferred model of democracy is one where citizens stay out of the kitchen and entrust the job to professional cooks.

This minimal conception of democratic government as elections fails to harness fully the nation-building potential of democracy that PAP ideologue and wordsmith S. Rajaratnam wrote into the Pledge, that and his editor Lee Kuan Yew did not remove.

Political capital

Singapore’s illiberal approach to democracy creates another problem relevant to today’s theme. It is behind certain policy failures that have depleted the political capital the PAP needs to fulfill its nation-building mission.

Recall that the PAP has always maintained that it’s more than just another political party; it is a national movement. And I don’t think this is just hype.

One of the positive side effects of one-party dominance is that the PAP straddles the class, ethnic and sectoral spectrum. We don’t think of the PAP as the party of any one group, unlike multi-party democracies where competition produces market segmentation, such that parties tend to have narrower bases – business or worker, rural or urban, religious or secular, for example. The PAP has tried to occupy the full spectrum.

The PAP’s character as a national movement has been an important resource in Singapore’s management of difference. Because in intra-societal disputes, people generally felt they could trust the referee, even if not everyone liked him. To the extent that the PAP was dictatorial, at least it was an equal-opportunity dictator.

Thus, one of the traditional strengths of the PAP has been its reputation as a generally neutral arbiter among competing communities.

I say this has been a “traditional” strength because I don’t think it’s as true today as it was before. The PAP’s mismanagement of immigration tarnished its reputation as the protector of ordinary Singaporeans’ interests. It has allowed nativists to claim some of that space.

When disaffection finally bubbled over in the 2011 general election, the government finally moderated its policies. But lasting damage had already been done to its moral legitimacy.

Two signal events, each unprecedented in its own way, revealed the extent of that damage.

First, in 2013, the government’s Population White Paper and its 6.9 million population planning figure was rebuffed even in Parliament. The government could not carry the ground, because people simply did not trust that it was acting in their interests.

Then, in 2014, Philippine nationals in Singapore had to abort their Independence Day celebration at Orchard Road on the advice of police after online protests. This is a country that is trusted to hosted some of the world’s most sensitive meetings, like the Shangrila Dialogues and the Trump-Kim Summit, so it is inconceivable that the police could not guarantee the safety of this party at Ngee Ann City.

The cancelling of the event was an admission of the government’s depleted political capital with regard to the immigration issue. It knew what the right thing to do was, but it could not carry the ground.

The government may have learned to treat immigration policy more sensitively, but it does not seem to want to get to the bottom of how it made this mistake in the first place. If it did, it would see that the stifling of immigration debates over the preceding one or two decades was a key reason why unhappiness had been allowed to build up.

Anticompetitive tendencies

Of course, the government says that it consults internally and externally, and that important decisions are open to debate. But just as many countries claim to believe in free trade but in practice operate a whole regime of regulations and tariffs to protect their markets, the Singapore government ensures that the trade in information and ideas never challenges its monopoly.

And it’s unclear how this anticompetitive approach helps Singapore or the PAP itself in the 21st century.

We know, in every other enterprise, how stress-testing through vigorous competition brings out the best in people and organisations, and how external scrutiny and transparency are the safest checks against abuse. It’s hard to see why these commonsense rules don’t apply to government and politics, where instead a dominant monopoly that is its own regulator is somehow supposed to be better for stakeholders.

This model has already compromised the quality of decision making and led to an unnecessary, avoidable depletion of the political capital the government needs to serve its nation-building role. It is also at odds with the clarion call contained in our Pledge, that we the citizens of Singapore are fellow nation-builders.

The 4G agenda

This event, like other recent IPS conferences, is a showcase of Singapore’s 4th Generation leadership. I hope 4G is not just the old operating system in a shiny new body, but a major upgrade that fixes bugs we’ve lived with for too long.

In the next leadership turnover, it would be nice if our leaders were so confident in themselves and their product that they would be prepared to lower the protectionist barriers around the marketplace of ideas; and to subject themselves and their ideas to constant stress-testing.

Equally overdue is a leadership able to model an enthusiasm for multiculturalism deeper than the superficiality of colourful costumes and spicy cuisine, not just to appeal to tourists but more importantly to get Singaporeans to see diversity mainly as a source of vitality and not always a vulnerability.

Until we see our glass as more than half full, as mainly a strength with some accompanying risks, rather than as a massive liability with some incidental benefits like batik and cendol, we are not going to live up to our Pledge.

Q&A – VIDEO

Comments are closed.